Ethos and the Schwartz theory of basic values

Our "field of responsibility" framework maps neatly onto the Schwartz theory of basic values, but suggests something critical may be missing.

The Theory of Basic Values

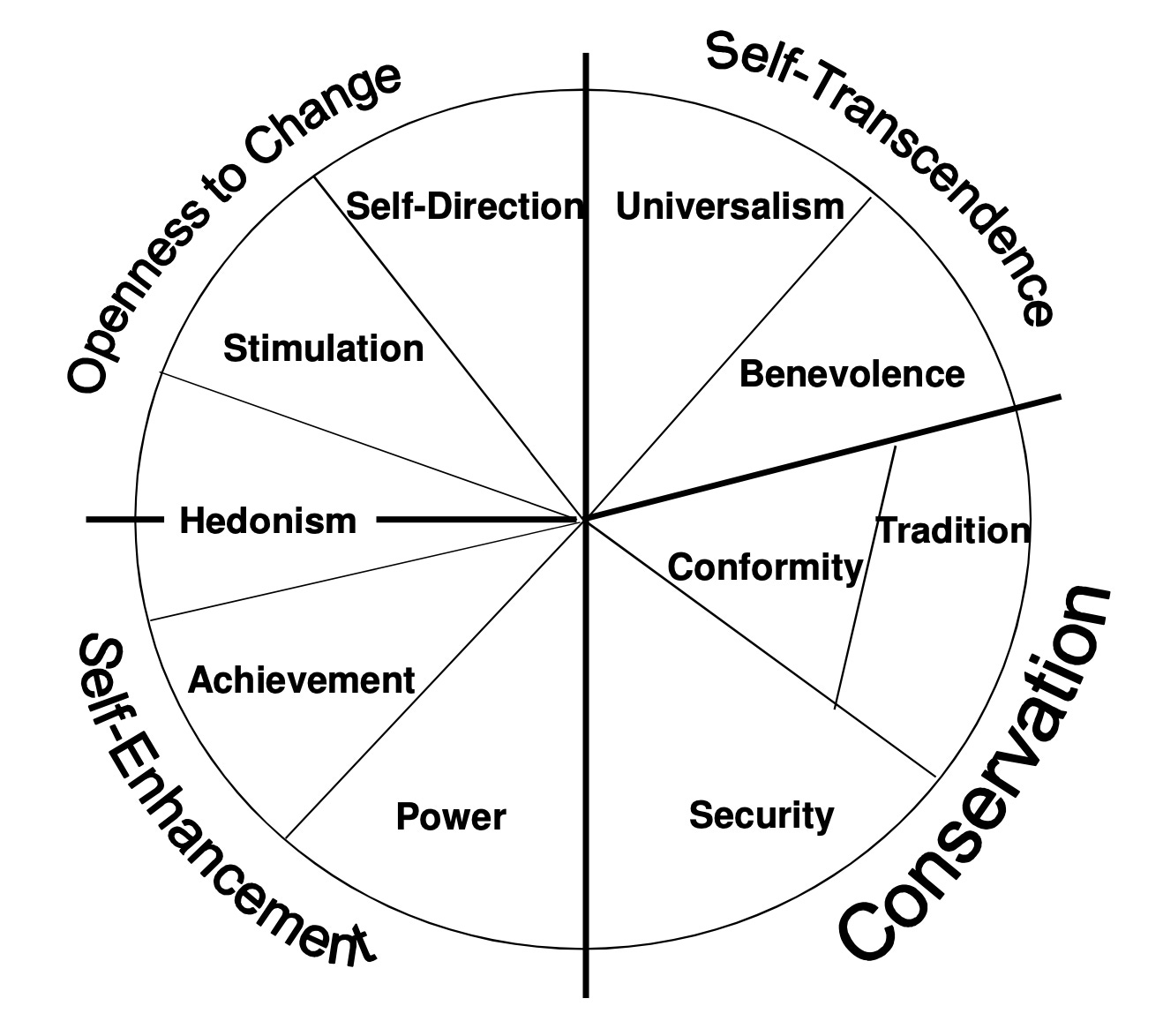

Schwartz's theory of basic values proposes that there are ten universal values that guide human behavior and serve as guiding principles in shaping individual and societal decisions. These values are organized into four higher-order categories:

Self-Transcendence values (universalism and benevolence) emphasize the welfare of others, concern for social justice, and the protection of nature.

Self-Enhancement values (power and achievement) prioritize personal success, dominance, and control over others.

Openness to Change values (stimulation, self-direction) promote innovation, creativity, and autonomy.

Conservation values (security, conformity, and tradition) prioritize order, stability, and preservation of existing societal norms and traditions.

According to Schwartz, these values are biologically and culturally rooted and can be observed across different cultures and societies. He also suggests that individual values can be ranked in importance and that this ranking reflects an individual's priorities and goals, which in turn influences their behavior and decision-making processes.

What are values

Schwartz distinguishes values from other related psychological and social phenomena through 6 key features:

Values are beliefs linked to affect - people are emotionally impacted in situations where their values are expressed or threatened

Values motivate action by referring to desirable goals

Values transcend specific actions and situations

They serve as standards or criteria for evaluating actions, people, events and attitudes

People vary in the importance they give to different values

It is the relative importance of a value that motivates action

Schwartz believes values are probably universal because they are "grounded in one or more of three universal requirements of human existence with which they help to cope... needs of individuals as biological organisms, requisites of coordinated social interaction, and survival and welfare needs of groups"

The Circular Structure of Values

Recognizing that "actions in pursuit of any value have consequences that conflict with some values but are congruent with others", Schwartz portrays the values on a circle in order to indicate the relative conflict or compatibility between them.

For example, pursuing (personal) achievement is usually in conflict with benevolence, but also usually compatible with pursuing power.

Values on opposite sides of the circle tend to conflict, while those adjacent with each other are more mutually compatible.

It's important to note, also, that Schwartz sees the partition of this circle into 10 discrete values as somewhat arbitrary. This circle represents a continuum, and more fine- or course-grained distinctions between values are possible.

Schwartz Value Survey and the Portrait Values Questionnaire

Schwartz offers two different ways of measuring the relative importance of values. The Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) provides a list of 57 words - 30 nouns and 27 adjectives - representing different values that participants are asked to rate in terms of relative importance "as a guiding principle in MY life" on a scale between 7 (of supreme importance) and -1 (opposed to my values)*

* The labelling of the scale is interesting from a survey design perspective: 7 (of supreme importance), 6 (very important), 5, 4 (unlabeled), 3 (important), 2, 1 (unlabeled), 0 (not important), -1 (opposed to my values).

The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) provides verbal portraits of 40 people, and respondents are asked to answer the question: “How much like you is this person?", with responses ranging from ‘very much like me’ to ‘not like me at all’.

These portraits characterise an individual aspirations and goals, rather than their traits (see the distinction below).

For example: “Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to him. He likes to do things in his own original way” describes a person for whom self-direction values are important. “It is important to him to be rich. He wants to have a lot of money and expensive things” describes a person who cherishes power values.

Schwartz claims the PVQ provides a way of testing the validity of values in cross-cultural contexts.

The Universality of the Basic Values

The 10 basic values have been validated in 82 different countries - with representative national samples from 32 of those. But it's important to be clear about what that means.

This means that 92% of people distinguish between these 10 values when articulating what's important to them (or what sort of person shares their values in the Portrait method), and where they do fail to make a distinction, it is between adjacent values (eg security and power), preserving the overarching circular structure of the model.

It does not mean that people share the same values - on the contrary, the strength of the model is precisely that it can be used to accurately describe variations in the relative importance of values to different people.

Schwartz's model, then, is a kind of grammar of values - or in Kantian terms, the transcendental categories of moral perception. To understand values as humans do, is to understand these categories and the proximity or tensions between them. It is to be able to distinguish hedonism and tradition, and know that they stand in opposition to each other, regardless of which of these one values more highly.

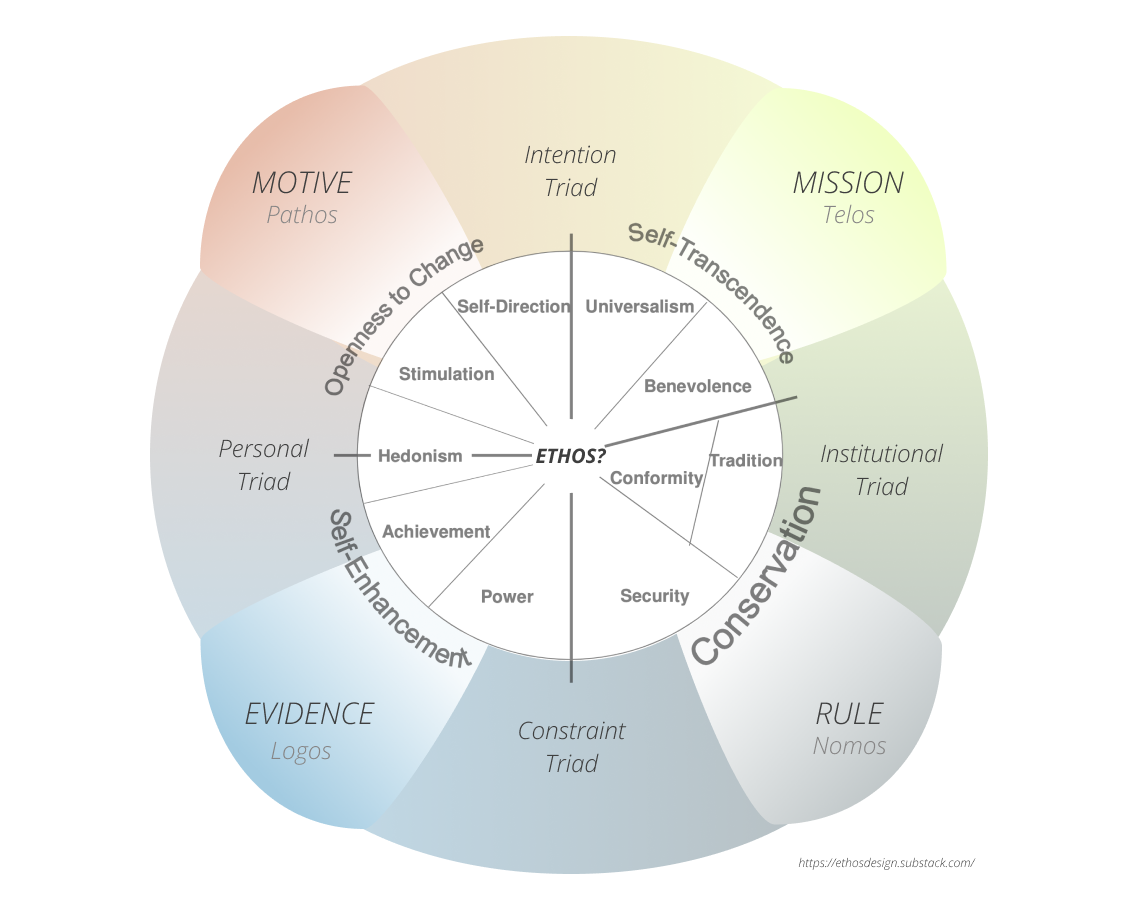

Schwartz's model maps onto our field of responsibility

Remarkably, the "field of responsibility" framework, which we introduced to capture the relationship between ethos and related philosophical concepts, maps neatly onto the Schwartz theory of basic values. Even the orientation of the circular structure is the same.

This is valuable for a number of reasons

It provides empirical support for the distinct territories that the field of responsibility framework maps out

It reinforces the idea that we can do values analysis in a team context, as the framework helps articulate those values in ways that are more familiar to team contexts

We can now leverage the considerable work done in the field on accurately assessing the values hierarchy for an individual - including valid and reliable survey questions and measurement techniques, like the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) and the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) - in order to make explicit the values embodied in a team's behaviours and context.

Where is Ethos?

The comparison is also intriguing from a theoretical perspective.

Our framework was not based on any theoretical conception of value, but on the senses of ethos in the philosophical tradition, and in particular, which terms ethos is juxtaposed with - namely, pathos, logos, telos and nomos.

But there is no conception of ethos within the Schwartz theory of basic values.

Distinguishing values from related concepts

One very useful aspect of Schwartz's work is distinguishing between values, on the one hand, and attitudes, beliefs, norms and traits, which are often conflated with them. Schwartz differentiates these based on how they vary between individuals.

Values vary in importance, that is, different people grant more or less importance to the value of security.

Attitudes are "evaluations of objects as good or bad, desirable or undesirable" and vary by being more or less positive or negative

Beliefs are "ideas about how true it is that things are related in particular ways" and they vary by how certain we are that they are true or false (ie they vary in confidence or certainty)

Norms are "standards or rules that tell members of a group or society how they should behave" and they vary in how much we endorse them, ie whether we accept or reject them

Finally, traits are "tendencies to show consistent patterns of thought, feelings, and actions across time and situations". Traits vary in how reliably and intensely people exhibit them. Traits are easily confused with values - because they often have the same name, one can be habitually obedient (i.e. exhibit obedience as a trait) without seeing obedience as important (i.e. grant import to obedience as a value). The distinction is particularly important, as it allows us to make sense of how we can aspire to embody values in our patterns of thought, feeling or action in the future, that we don't yet embody today.

Schwartz sees values as causing other phenomena, never as caused by them.

"Values underlie our attitudes; they are the basis for our evaluations."

"Our values affect whether we accept or reject particular norms."

The distinction between traits, norms and values reveals a kind of idealism in Schwartz's work - treating values that we aspire to embody as foundational compared to traits, patterns of thought and behaviour that we actually embody, or norms, standards of behaviour that we are prepared to enforce.

Similarly, when Schwartz says that "values underlie our attitudes" as the "basis for our evaluations", he's saying that the reasons we give for our attitudes don't just explain, but actually cause our attitudes.

If the last 50 years of psychology has taught us anything, it is that we should hesitate before treating reasons as effective causes of patterns of thought or behaviour.

This doesn't make them any less real - reasons make a difference, because asking for and giving reasons is fundamental to earning the recognition of others as a full participant in a human community. Schwartz's map of 10 basic values is a map of the so-called "space of reasons" - it maps the reasons that humans will recognize other humans can legitimately give to explain their behaviours and attitudes.

In this sense, it is no different from the phonetic space of speech - which is the collection of sounds that members of our community can and do use to communicate thoughts or attitudes with each other. This space is smaller than the space of all possible sounds, and remaining within this smaller phonetic space (and obeying some basic rules of how they can be combined) signals to others that we are part of the same linguistic community. What's more, conforming to this constraint in our speech provides others with sufficient justification for attempting to understand what we are trying to say, even if none of the things we say make sense. This is one of the reasons it makes sense to try to understand a baby, but not to understand a kettle. Both make noise, but only one of them is interpreted as trying to speak.

In the same way, respecting the structure and content of the basic values Schwartz describes enables us to demonstrate we belong among a community of beings who can understand and be understood in terms of responsibilities.

To be continued…